KarstCare – Cavers caring for caves

Karstcare is a Wildcare group who contribute to cave management in Tasmania, enabling cavers to minimise the impact of pursuing their passion.

Whilst they do the odd surface weed eradication/re-vegetation project (just to get some vitamin D!), their workplace is predominantly underground and requires specialist skills. Sometimes, the worksite may be 2 hours or more into a cave!

Since the group’s inception in October 2000, they have contributed over 4,200 hours to karst management – not counting planning, meetings and travelling.

This article, by President Dave Wools-Cobb and Great Western Tiers Karst Ranger, Chris McMonagle, outlines a recently completed project in the Mole Creek Karst National Park.

- The main chamber – Genghis Khan Cave

A VERY SPECIAL AREA

The Mole Creek Karst National Park (MCKNP) is a collection of several disjointed parcels of land which contain some of the most highly regarded karst systems in Australia. Unlike many other cave systems in Australia, the caves within the MCKNP are in a relatively pristine state and as such are extremely popular destinations for recreational cavers from both Australia and overseas.

CAVER INVOLVEMENT IN PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT

Many of these caves are located within the TWWHA and are managed by the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS). A crucial aspect of the current management process involves an on-going process of stakeholder consultation to assist land managers with cave access planning and recreational caver management. This stakeholder consultation underpins the decision making process when determining what areas of a given cave can be visited, and by whom. Tasmanian recreational caving clubs contribute significant resources to this process, which can include cave mapping, ‘in cave’ cave management activities, attending planning meetings and extensive document reviews, culminating in a document called a ‘Cave Zoning Statement’. This process has seen the successful development of several approved zoning statements for a multitude of karst systems across many of the PWS managed karst systems in Tasmania.

- Genghis anthodites

- Genghis anthodites

One of the first caves in Mole Creek Karst NP to have a zoning statement approved was ‘Genghis Khan’ Cave which is particularly popular with cavers visiting Mole Creek and is quite renowned for its anthodites – one of the best displays in Australia. The cave is generically part of the spectacular Kubla Khan Cave, however no navigable connection has ever been found between the two systems.

Genghis Khan is legislated as a Restricted Access Cave and as such most of it has been zoned ‘Limited Access’, requiring a PWS issued permit to members of the Australian Speleological Federation (ASF) clubs or equivalent. Three sections of this cave are considered to be too delicate to enter, so are zoned ‘Special Management’, with access usually only granted for specific scientific purposes (this requires a higher level of approval before an access permit can be issued). Two of these areas can be ‘viewed’ from

string lined barriers with explanation signage.

Contributing to this zoning process, Alan Jackson has produced a new digital map of the cave, with field work assistance from several members of various Tasmanian caving clubs.

Of particular concern was the lack of caver management inside the cave. Once a permit has been granted and a key for the gate obtained, cavers could access most of the cave (except the Special Management Zone) with no real guidance as to where to walk. This resulted in mud tracking over several surfaces of the cave which can have a negative impact on both the aesthetic features and formation processes of the system.

Northern Caverneers members Janice March and Dave Wools-Cobb submitted a proposal to PWS for a practical project to minimise this mud tracking in the regularly visited areas of this cave.

INGREDIENTS

Over several working bees, a cleanup project was successfully completed thanks to the following:

- 300m of poly pipe

- 1250l of water

- 200m of string line

- 9m of plastic matting

- Our band of twelve caver volunteers who contributed

- 135 hrs of work

- Great Western Tiers Karst Ranger, Chris McMonagle

- NRETas Karst Officer, Rolan Eberhard and,

- The tremendous effort of the PWS Prospect fire crew in providing the water.

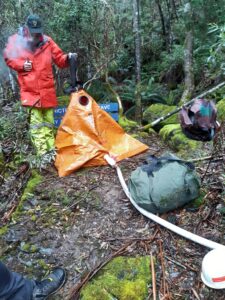

Gear for Genghis cleaning

METHODOLOGY – STAGE ONE

On an initial visit, and in consultation with NRETas Karst Officer Rolan Eberhard, a route was determined, and string line positioning commenced. Measurements were taken of areas unable to be cleaned, for future placement of plastic tube matting, and two boot wash bins with brushes were positioned. Reflectors were placed about 10-12m apart up a sloping flat slab as it was decided these were more practical than string line. The counter-clockwise route returned in a loop to a junction with the initial route earlier descended.

Two old carbide dumps were also cleaned up: these dating decades back to a time when carbide lamps were used and caver attitudes were less environmentally aware.

WE HIT A SNAG

Once a formalised route had been delineated, the next major obstacle to progressing the project was the availability of water to clean the route. Cave substrates often require significant amounts of water in order to wash and clean the rocks and formations of mud and debris that is spread by recreational cavers within the cave system. Most caves have a good supply of water that can be utilised within the cave, however Genghis Khan is a relatively dry cave, which meant that any water to be used would need to be physically carried to the site by the individuals undertaking the works.

- Bladders, pumps and pipes – Photos provided by Chris McMonagle

STAGE TWO – PWS STEPPED WITH A CREATIVE SOLUTION

In an attempt to reduce the burden on the cave cleaners to have to carry hundreds of litres of water into the system in backpacks, Great Western Tiers Karst Ranger, Chris McMonagle investigated the possibility of utilising the equipment and skills of the PWS fire crew to assist in water delivery to the site.

Remote fire crews regularly use remote water supplies when fighting wildfires in summer, by utilising transportable bladders, collar dams and high powered portable pumps to transfer and store water in inaccessible areas. These crews use the winter months to conduct prescribed burns and retrain their skills (and their equipment) for the upcoming season, and as such saw the proposal to deliver 1000 litres of water to cave entrances on top of a 100m high ridge in a forested area as good chance to train new staff, refresh their pump skills and test their equipment in a ‘relaxed’ environment.

PWS staff from the Prospect based Fire Crew were engaged to provide water in 500 litre collar dam bladders positioned immediately outside the entrances to both Kubla Khan and Genghis Khan caves. This involved carrying up the collapsed water bladders, then rolling out several hundred metres of water delivery lines to enable water to be pumped several hundred metres from a vehicle access track up the hill and into the bladders. Karstcare volunteers were not present during this event, however, greatly appreciate that it would have been a considerable effort.

NEXT ….

After the water was delivered, cleaning of the route commenced by Karstcare members. This involved positioning about 120m of 12mm poly pipe from the collar dam down into the cave with frequent ‘T” joiners enabling two teams to clean at the one time. Each junction was clamped on both sides of the joiner, with frequent taps positioned to control water flow.

- Area A before matting

- Area A with matting

Cleaning involved wetting the substrate (either limestone rock or some type of formation) then scrubbing with brushes and hosing again; a scrub/spray/scrub technique. Any area that drained towards flowstone rather than down into the rockfall substrate was filtered with towel dams. This cleaning is slow arduous work, and the teams end up extremely wet – perhaps more than the surfaces they are cleaning! Tube matting was then placed in two areas and the volunteers measured another area for future matting placement.

Unfortunately with two teams working at once, the water did not last long enough to complete cleaning.

The separate (but nearby) Kubla Khan Cave project (cleaning Pitch 1 & 2) only used about 250 litres of water, so we positioned 20m of fire hose and about 180m of poly pipe from its bladder down to the bladder situated at the Genghis Khan Cave entrance.

On the subsequent working bee, the pressure of approximately 70m of head was incredible, requiring clamps at every poly pipe junction, however the ability to shift mud from rock surfaces was amazing. Unfortunately, we again ran out of water before completing the cleaning. Time was spent positioning flat rocks over a particularly muddy area in preparation for plastic matting cover and more flat rocks on some muddy natural steps on a climb. In this way, we hoped to lessen mud picked up by boots in the future.

AND AGAIN

A request was made to the fire crew responsible for delivering the initial 1000 litres of water to replicate the task, which was eventually undertaken (once their prescribed burning activities were completed for the year). As soon as the water was available, we had a final working bee to complete the cleaning.

Fortunately, the top boot wash bin is situated under a regular drip line, so we filled the lower bin and left several filled water bladders for future use. More tube matting was positioned over a particularly bad muddy section giving access to a viewing area that is very photogenic. With water remaining, some of the lower areas were re-cleaned and a second viewing area provided, within string line barriers.

- Area B before cleaning

- Area B after cleaning

Updates were submitted for the PWS “Note sheet” for visitors to Genghis Khan Cave. Our delineated route now gives good access to most of the cave with minimal impact. There are two other areas of the cave that are particularly beautiful however do not involve much mud, so hopefully these will remain in good condition.

The total cost of infrastructure left in the cave would only be about $250. This series of working bees demonstrates that apart from considerable labour, and by thinking ‘outside of the box’, a low budget project can achieve a great deal. Genghis Khan Cave can be visited well into the future with minimal impact to its outstanding natural values.

Photos by Dave Wools-Cobb (unless otherwise stated).